A Guide to Groundwater: Earth’s Hidden Freshwater Supply

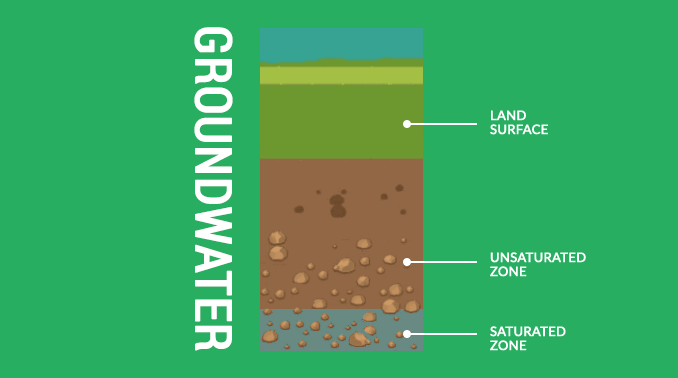

DEFINITION:

Groundwater is water stored underground in the cracks and spaces in soil, sand, and rocks. It’s stored in areas called aquifers and can be brought to the surface through wells or springs.

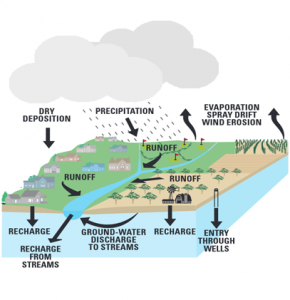

How Groundwater Works

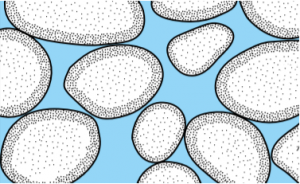

Groundwater fills pore spaces

Groundwater doesn’t exist as a huge lake underground. Instead, it fills in tiny pore spaces within rocks, sand, and soil.

So groundwater is more like a sponge with rock and sand. These pore spaces with groundwater are the “saturated zone” or “aquifer”.

Despite the popular belief that groundwater exists as a huge lake underground, water actually exists in tiny pore spaces within rock and soil beneath our feet.

Groundwater wells pump water

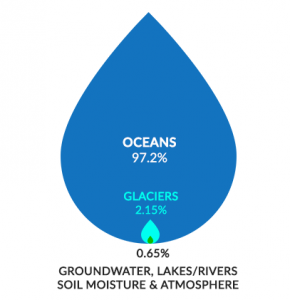

Because groundwater is below the surface, we use wells to pull it out. The water we draw from a well was once precipitation that fell as part of the water cycle.

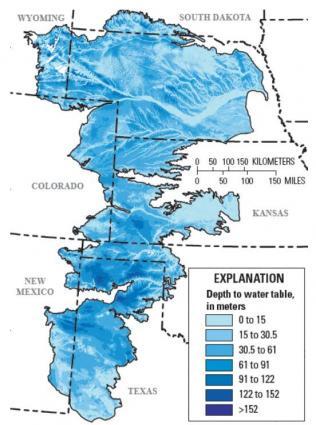

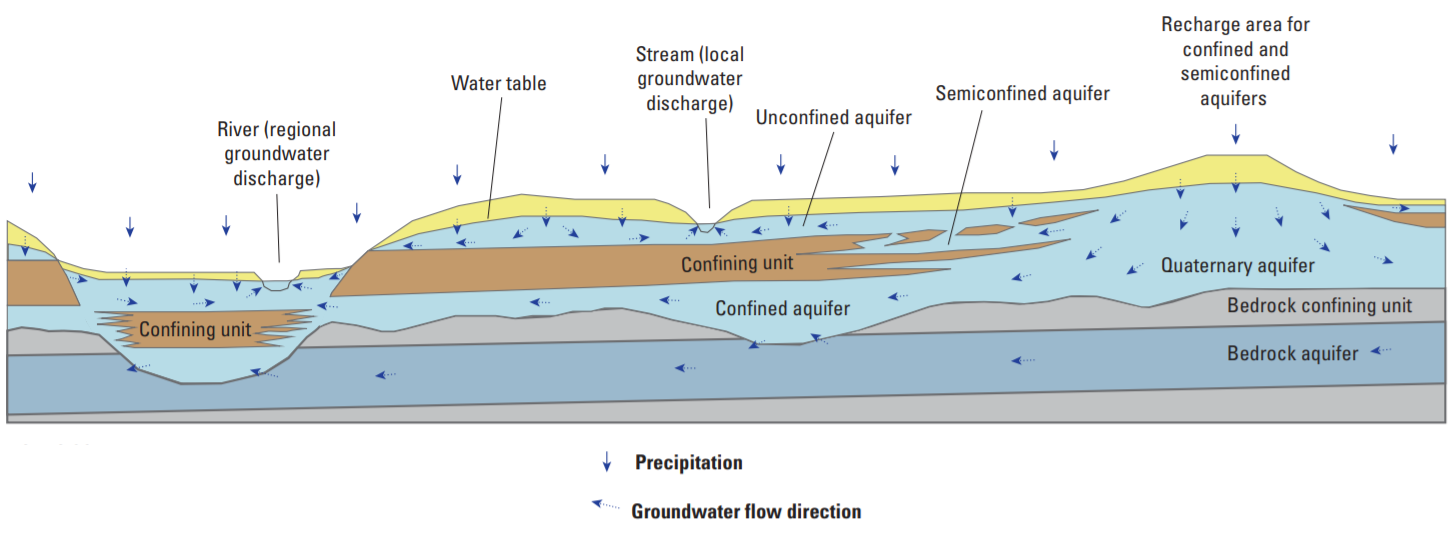

Aquifers can stretch for miles

Aquifers can stretch for miles serving hundreds of groundwater wells. For example, the High Plains Aquifer extends from South Dakota to Texas.

All water wells drawing from the same aquifer are connected. So when you pump water from your well, it affects other people miles away.

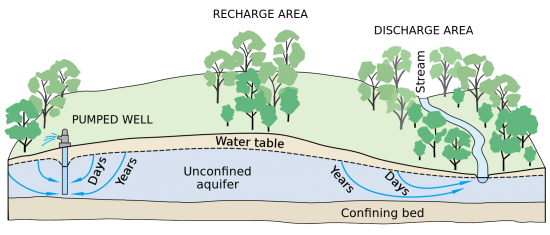

Rain naturally recharges groundwater

Precipitation seeps into the ground. Over time, it fills in the pore spaces in the ground.

Naturally, big particles like leaf chunks that can be found in streams don’t exist in groundwater.

Aquifers can go dry when they are not recharged.

Rainwater recharges aquifers by infiltrating the ground surface.

Sedimentary rocks make great aquifers

Sedimentary rocks like sandstone and limestone have faster groundwater recharge rates. They make the best aquifers because these types of rocks have connected pore spaces.

When it rains, water can easily travel through. The key to recharging groundwater is the “porosity” of the surface. Porosity measures how much empty space there is between pore spaces of rocks.

But igneous and metamorphic rocks restrict groundwater recharge because pore spaces have been squeezed away. This is due to the nature of how metamorphic and igneous rocks form.

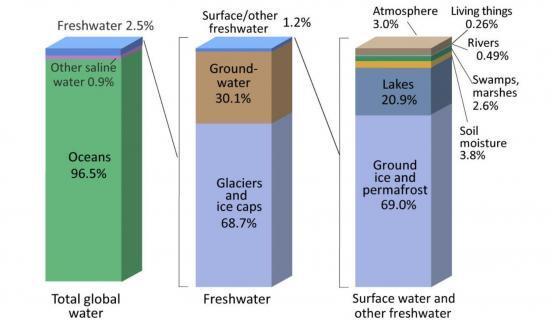

Groundwater in Numbers

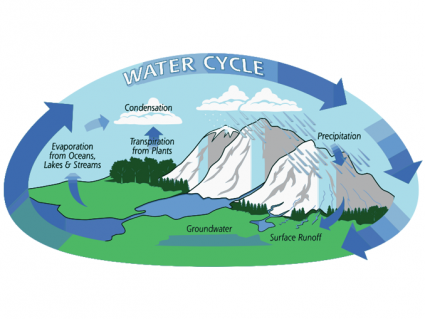

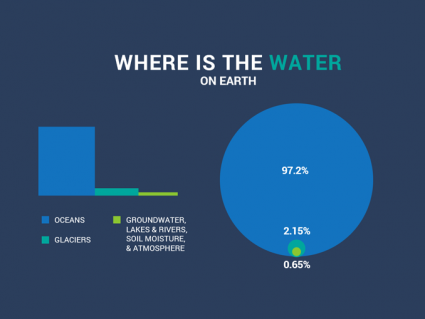

The big picture of groundwater

Groundwater is less than 1% of the total water on Earth. About 0.65% of total water on Earth is groundwater.

- About 0.65% of total water on Earth is groundwater.

- Groundwater is the second largest source of freshwater.

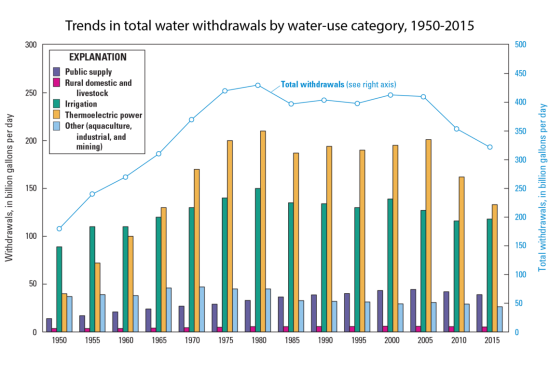

- We use groundwater mostly for drinking, irrigation and thermoelectric power.

Groundwater is the second-largest source of fresh water after glaciers. But if you compare only freshwater sources, groundwater has more than 60 times the amount as lakes and streams (combined).

Uses of groundwater

Large cities don’t rely on groundwater because there’s not enough to supply it. Instead, municipal areas use groundwater mostly for drinking and irrigation.

- THERMOELECTRIC POWER: Thermoelectric power generation uses groundwater to cool down equipment.

- IRRIGATION: Irrigation sprays crops to help them grow.

- DRINKING WATER: Groundwater provides drinking water for millions mostly in rural areas.

Types of Aquifers

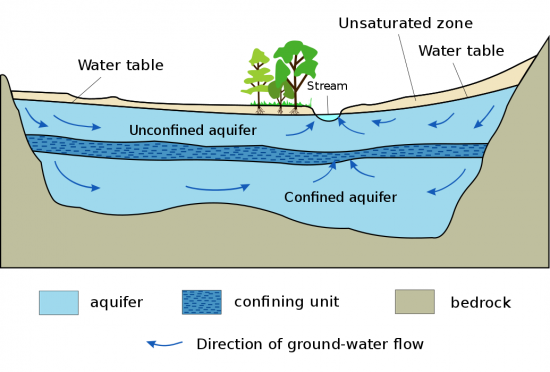

Confined vs unconfined aquifers

The two types of aquifers are:

- Confined aquifers

- Unconfined aquifers

The main difference between the two types of aquifers is where it’s located.

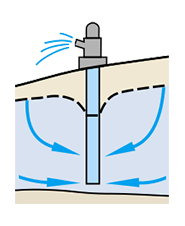

Confined aquifers have an impermeable layer

Confined aquifers have an impermeable layer preventing water from seeping into the aquifer. Generally, rainwater recharges this type of aquifer at a location farther away from where it’s more porous.

ARTESIAN WELLS: Artesian wells tap into confined aquifers. The confined layer creates pressure squeezing the aquifer. When you tap into an artesian aquifer, the pressure pushes the water upward. If the pressure pushes the water all the way to the surface, it creates a “flowing well”.

This is kind of like holding a wet sponge in a plastic bag. If you poke a straw in the bag and squeeze, water will squirt out. The bag is like the confined layer squirting out artesian water.

Unconfined aquifers have no restrictive layers

Unconfined aquifers do not have a layer that restricts water flow. So if you dig beneath your feet, you’d directly hit the water table

After a rainfall, water seeps into the ground directly into the saturated zone. Unlike confined aquifers, these types of aquifers don’t have a layer that restricts flow into the ground.

WATER TABLE: The top of the saturated zone is called the water table. Generally, unconfined aquifers have a water table closer to the ground. If the water table is high, groundwater can flow to the surface naturally in springs, lakes, and wetlands.

Groundwater Sustainability

If we don’t take care of groundwater, we might lose it. For example, here are some ways we can damage groundwater:

- OVERUSE: Pumping too much can make aquifers go dry.

- CONTAMINATION: We can contaminate if chemicals enter.

- CLIMATE CHANGE: Climate change will impact groundwater recharge.

Aquifers can run dry

When you extract too much water and too often, aquifers can run dry. For example, the Ogallala Aquifer stretches from Nebraska to Texas.

OGALLALA AQUIFER: From 1980 to 1995, farmers were pumping too much water to irrigate their fields. During this period, groundwater withdrawal was much faster than it was being recharged.

But as farmers improved their irrigation, they lost less water from evaporation. Eventually, it began to recharge at a more stable rate.

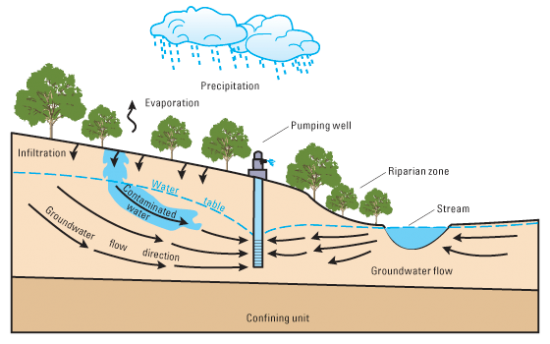

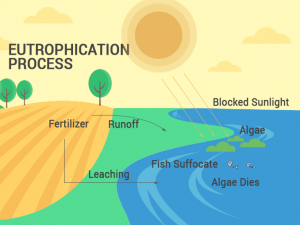

Pollution can contaminate groundwater

Over time, water sinks into the ground through layers of rock that naturally filter groundwater. This makes groundwater some of the purest water available.

But human activities can add contaminants to groundwater. Once contaminated, it’s difficult or nearly impossible to return to its previous state. Here are some examples of groundwater contamination:

- FERTILIZERS: Fertilizers and pesticides can leach into groundwater from over-fertilization

- PETROLEUM: Petroleum can contaminate groundwater from gas stations or storage tanks

- WASTE: Septic tanks and waste disposal sites can leak into groundwater

- CHEMICALS: Naturally occurring chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide can end up in

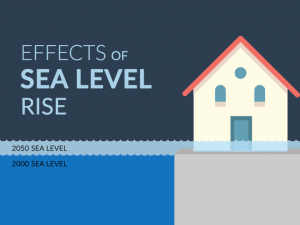

Climate change will impact groundwater

Overall, the main consensus is that the climate is warming. This means that climate change is set to become one of the biggest influences on groundwater recharge.

Although the effects of climate change are still in question, one of the biggest questions is total precipitation.

Wet and dry periods will impact groundwater for human usage and natural recharge rates. And the water table will go up and down in response to climate change.

Importance of Groundwater

Aquifers are important because they can supply water for extended periods of time. Particularly during periods of drought, we can draw in times of need.

Despite the difficulty of pumping water out from the ground, extracting too much can cause it to yield less water. Eventually, it can reach a point where it runs dry.

“Aquifers are like a rainy day fund”

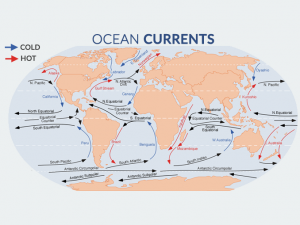

Groundwater is a major source of steam flow

Groundwater and surface water are connected. Discharge from groundwater adds to the total flow of streams and rivers.

But groundwater pumping can reduce the flow of groundwater to streams. This streamflow depletion can impact the availability of aquatic ecosystems in surface water.

A key indicator of health

Lastly, authorities keep tabs on how much groundwater is pumped. By tracking water use, they monitor risks to groundwater.

For example, groundwater levels indicate the amount available in aquifers. Finally, water quality assesses the risk of contamination in groundwater.

Otherwise, we want to hear what you have to say! Please use the comment form below and let us know what your thoughts are about anything related to groundwater.

I have a question… Theoretically speaking, if two Wells are drilled 5 mi apart from the same elevation, one hits groundwater at 50 ft and the other at 150 ft, will the one at 150 ft have cleaner water