El Niño vs. La Niña: What’s the Difference?

“The El Niño and La Niña phenomena are part of a 3 phase cycle that occurs in the Pacific Ocean. The other phase is simply “normal” conditions.”

- EL NINO: El Niño is the warming phase of the waters in the eastern Pacific, off the coast of South America.

- LA NINA: Then, La Niña is the cooling phase.

Both phenomena disrupt weather and temperature around the globe. For example, they unpredictably create:

- Heat waves

- Floods

- Droughts

El Niño and La Niña peak around Christmas time and can last 9 months or longer. Then, it repeats again every 3-5 years or so. But how does El Niño work? And what causes El Niño? Let’s examine the El Niño phenomenon.

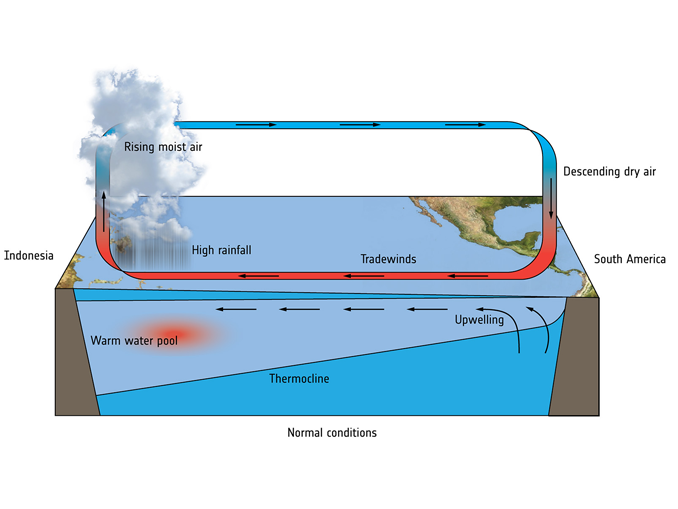

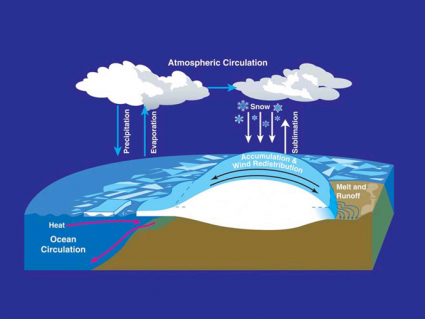

Normal Conditions

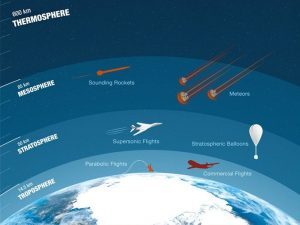

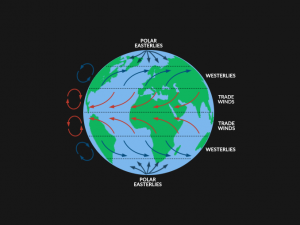

El Niño takes place in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. In normal conditions, Trade Winds blow from east to west. These winds push warm water like a conveyor belt to the coast of Asia and Australia. Then, warm water pools in the west of the Pacific Ocean. This causes the thermocline (top-to-bottom ocean temperature gradient) to deepen.

But along the coast of the Americas, cold water from deeper down in the ocean replaces the warm surface water that is transported to the west. This process of deep, cold water rising to the surface is called “upwelling”. So in normal conditions, there’s a big temperature difference from east to west in the Pacific Ocean.

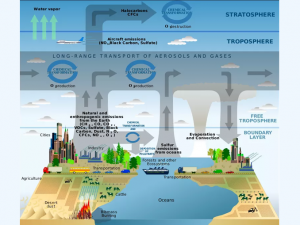

In the western part of the Pacific Ocean, the warmer water adds extra heat to the air. Then, this causes the air to rise generating clouds and rainfall in a self-feeding cycle. First, we have warm moist air rising in the west. Secondly, dry cool air descends on the eastern side of the Pacific Ocean. This type of atmospheric circulation continues until El Niño begins.

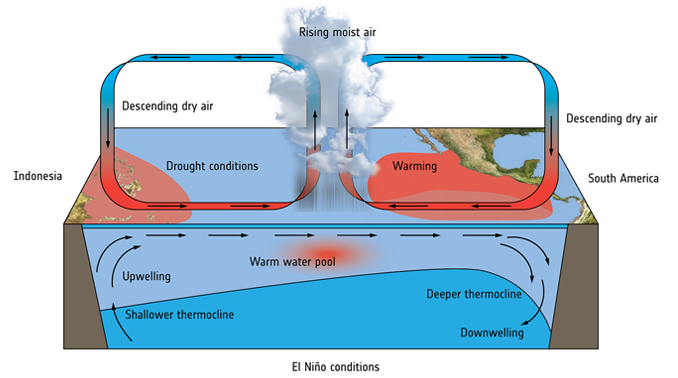

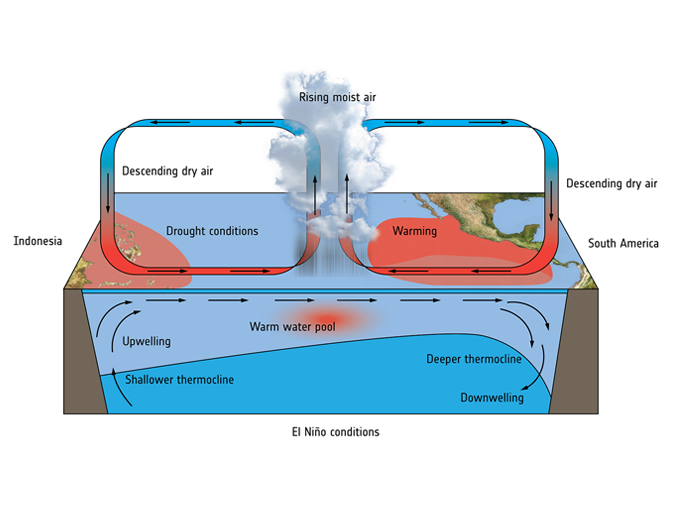

El Niño

Every 3-5 years, El Niño is triggered by a weakening of west-blowing Trade Winds. As winds weaken, it results in less warm water to the west. Consequently, there is also less cold upwelling water off the coast of the Americas.

So, there’s less push of warm surface water to the west. On top of that, there’s less upwelling on the eastern side. As a result, warm water piles up centrally in the Pacific Ocean disrupting the normal temperature balance between the eastern and western Pacific.

During El Niño, the increased water temperature drives rainfall (which we measure with weather recording devices such as rain gauges). If you have concentrations of heat, it forms pressure systems that build storms. This is why the equatorial Pacific has increased rainfall and winds. Then, these conditions impact global weather conditions in other regions around the world.

La Niña

After El Niño reverses back to normal conditions, it can dip into its counterpart La Niña. La Niña is basically El Niño in reverse.

Instead of a weakening of Trade Winds, La Niña experiences a strengthening in equatorial air circulation. La Niña pushes warm water even further west. Then, it increases the upwelling of colder water in the eastern Pacific decreasing temperatures there.

Similar to El Niño, La Niña can have a major impact on global weather as well. La Niña tends to have the reverse effects of El Niño. For example, you get drought conditions in countries near the eastern Pacific because the cooler water produces less rain.

How Does El Niño Affect Weather?

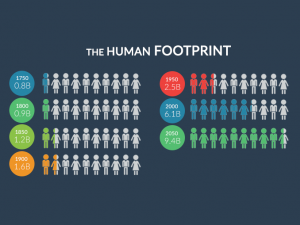

As part of the big picture, El Niño releases vast amounts of energy pushing up global temperatures. This is why El Niño years are often the warmest on record.

The main weather impacts from El Niño occur in the tropics. For example, here are some of the effects worldwide:

- FLOODING: Peru often experiences flooding.

- DROUGHT: India, Indonesia, and Brazil have drought conditions.

But El Niño can drive heatwaves, floods, and droughts outside the tropics too. It can affect virtually everywhere in the world directly. If not through the weather, it will at least have socioeconomic impacts.

Why Does El Niño Occur?

It’s still not fully understood what triggers the irregular El Niño conditions. But scientists believe there are several co-dependent factors that drive El Niño. For example, this includes the strength of Trade Winds and the push-pull of water movement.

The Coriolis Effect ultimately drives the overall flow of Trade Winds. But it’s the variations in concentrations of warm water that get moved by the Trade Winds.

It’s these non-static oceans and atmospheric conditions that make predicting the occurrence of El Niño difficult.

El Niño vs. La Niña: What’s the Difference?

El Niño and La Niña are classified as the two main weather patterns in the Pacific. These cyclical phenomena can have an effect on the climate, often causing heat waves or cold spells across North America and Europe.

However, El Niño and La Niña are not just weather phenomena—they’re also a very important part of the hydrologic cycle.

If you want to add a comment about El Niño and La Niña, the two weather patterns that affect the world, please drop a comment below.

I love your diagrams; they are very clear. But you posted two El Nino diagrams but no La Nina diagram. Can you please add a La Nina diagram. Thanks!

Why can’t commentators and broadcasters get their pronunciation correct? I believe Spanish speakers would say

La Nina = la neen-ah.

El Nino = el neen-ya (with a thing over the second n.)

The waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean are usually cold because a cold ocean current called the Peru Current flows along the Western Coast of South America.

Need a diagram depicting La Nina conditions. Thanks.

A wonderfully informative piece. Very happy to have found this website!

A massive pulse of hot water from the ocean floor (heated by magma from the Earth’s core) predictably originates in the same place at the onset of every El Niño on record. Hundreds of newly discovered (May 1, 2016) deep-sea hydrothermal vents located along the Mariana Trench, a “deep-sea canyon on the floor of the western North Pacific Ocean North of Papua New Guinea.” El Niño triggers the reversal of atmospheric circulation (trade winds) in the tropical Pacific Ocean, not the other way around.

I love this site. I’m glad I stumbled upon it.